A CHILL IN THE AIR

April 1st,1939. The spectre of an all-out war in Europe is looming. The Anglo-American writer and philanthropist Iris Origo – then owner of the La Foce estate in the Val d’Orcia – has just written the following words in her diary:

‘Chamberlain’s pronouncement about Poland has been received with unexpected moderation in the press and with some enthusiasm privately – as being likely to put a brake on Hitler.

A country neighbour (small farmer – a shrewd, sensible, elderly man) has just been to lunch, and has made no bones about expressing his disgust at recent events. He is particularly indignant at Mussolini’s phrase about peace being “a menace to civilization”. “What about Sweden and Norway?” he says. “Aren’t they more civilized than us? And happier?” (This is unexpected, he would not have said that five years ago.) He tells us that all his peasants, like ours, are terrified.’

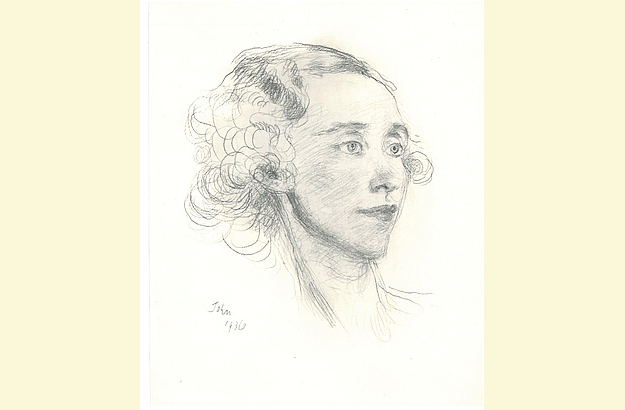

Iris Origo (1902-1988) wrote many memoirs, essays and biographies during her life. She is probably best known for Images and Shadows, The Merchant of Prato and the gripping War in Val d’Orcia, a 1943-1944 war diary originally published in 1947 by Jonathan Cape (London), and which I told you about in a previous article. The above excerpt, however, is from a pre-war diary that has only been rediscovered lately and published last year as A Chill in the Air: An Italian War Diary 1939-1940.

In this latest work, Iris Origo proves once again to be a most sagacious observer of the shifting political landscape surrounding her. Elegantly written and favourably reviewed by The New Yorker, A Chill in the Air may not be the usual happy-go-lucky holiday read, but it is a surprisingly relevant and thought-provoking book in current times, as well as an unsettling reminder that things in this world can go pear-shaped very quickly.

On July 20th, 1939, Iris is writing: ‘‘Have just been to tea with some charming anti-Fascists, the Braccis. They – and they say all their friends – are very pessimistic about the prospect of war and regard the optimism of Fascist circles as either propaganda or wishful thinking. Contessa Bracci, who has two sons of twenty-two and nineteen, is particularly depressed. “It would be bad enough,” she says “if they were fighting for something they believe in. But to know that they will be fighting for what they hate and despise…”’